Unwavering Words

This book is dedicated to my mother

Lan Anh Vuong

I want to tell my motherʼs story so her children, her childrenʼs children, and her nieces and nephews will know that if it werenʼt for my mother and fatherʼs courage, and later my motherʼs hard work, our family would probably not be in Canada enjoying privileges that only a highly developed country with one of the highest standards of living in the world can provide. Furthermore, I want future generations to understand that it was my motherʼs persistence, her refusal to settle for less, that lay the foundation for their lives. I want everyone to be as grateful as I am for the freedom he or she enjoys.

My mother has always believed that family is more important than anything else in the world, that family is irreplaceable, and all her youthful energy went into creating a better world for hers. She is my greatest mentor. This book is my way of thanking her for her foresight and courage, her love and devotion.

Amy Lee

Mother,

I have spent countless days and sleepless nights writing this book as my tribute to you for being the world’s greatest mother. I hope you like this surprise birthday gift I created for you.

Happy Birthday, Mom Much Love,

Amy

September 14, 2011

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Introduction

A Note to the Reader

PART ONE: Vietnam

PART TWO: In Transit as Refugees

PART THREE: Life in a Foreign Land

PART FOUR: Mother Alone

PART FIVE: Mother Remarries

Appendix

Lan Ang Vuong

Letter written by Tung Bun Lee

Immigration of Lee and Vuong Families

Lan Anh Vuong’s Children

- Julie

- Amy

- Eric

- Lisa

A Brief History of Chinese in Vietnam

Epilogue

Bibilography and Endnotes

Acknowledgments

One of the most important things my mother taught me is that to insure credit, I must build trust. No one else can do this for me. I must do it for myself. “When you promise something to somebody,” she said, “it automatically becomes a debt to that person, and that debt must be repaid in order to insure future credit.” To me, this also means that I must give credit where credit is due.

My motherʼs wisdom has been invaluable throughout my life and working career. I owe her a big debt and hopefully, this book will in some way help to repay that debt. But I could not have completed her biography without a number of othersʼ encouragement and help.

First of all, I would like to thank my brother Eric for his support and artistic contribution to the book. I would also like to thank my sisters, Julie and Lisa, my cousin Maggie, and two of my best friends, Kam and Pandora for their encouragement and advice. When I told my siblings and friends that I was nervous, that I didnʼt think that I had the qualifications to write a book, that perhaps I should hire a ghost-writer, they convinced me to write it myself. My “voice” should tell the story. My personal involvement, emotions, and feelings would make the biography more authentic.

I am also thankful that Yvonne Young agreed to be my editor. Over the last couple of years, Yvonne has not only been my mentor and teacher, she has also become a dear friend. I am so grateful for her personal support and professional guidance.

Last but not least, I would like to thank my three children, Kelvin, Jody & Deon who, two-and-a-half years ago, laughingly said that there was no way I could accomplish my goal because I lacked a formal education. Their doubt motivated me. When I hand them a signed copy of “Unwavering”, I hope they will learn from their mother what I learned from mine – “where thereʼs a will, thereʼs a way.”

Introduction

If there was an award for the worldʼs most amazing woman, daughter, sister, mother, and grandmother, my mom would be the recipient. She has been my idol since I was a little girl. She did not deserve the grief I gave her in my teens but, young and pig-headed, I did not think about her suffering. I knew her life had been difficult when she first arrived in Canada as a refugee, with a husband and four children, but I knew little about her pre-Canada years.

I learned about this time, during our sixteen-hour flight home from Australia in December 2008, when she spoke, for the first time, about the horrors she had been exposed to living in war- ravaged Vietnam. It was the longest, deepest one-on-one talk, we have ever had in our history together. We were both in tears as she described many scenes from her distant past. I am still amazed at some of the stories she told, especially those relating to the war and our escape from Vietnam, prior to the familyʼs arrival in Canada.

When we finally reached Canada, she said, life was not what she had dreamed it would be. She did not expect that, three years later, her father and husband would die of cancer within six months of each other and that she would have to raise four children herself. After his death, she chose to work long hard hours as a chef rather than accept welfare. She did not want her family to simply survive, she wanted her children to flourish.

Eventually she bought her own restaurant and, later, established herself as a builder and real estate entrepreneur. In eight years, she went from a poor widow to a self-made millionaire. She taught

her children through example and she taught us well. Inspired by her diligence and hard work, we were all worth well over seven digits by the time we were in our thirties, and she is proud of each and everyone of us.

I was so moved by the stories she told that I decided right then and there that I would write a book about her life. At the time, I had no idea what I was getting myself into. I had never been a good student and my writing skills were practically non-existent. I began to worry that I was not up to the task but, being my motherʼs daughter, I was determined to find a way. I returned to school and took writing courses. I forced myself to read and complete the first book Iʼve ever read cover to cover. I talked to my aunts and uncles. I interviewed my mother, although she had no idea that I would put her words in print. I researched and wrote and revised and then wrote and revised again. This project became a labour of love.

I see now that almost everything I know, I learned from my parents. They taught me how to think and solve problems. They showed me, through their example, how to be courageous and a leader. I feel robbed that I only had my father in my life for twelve years and yet, in our time together, he taught me that the most important thing to do is to be more, do more than others expect. I must not forget to mention that both my mother and father encouraged all their children to dream and to dream big.

Everything begins with a dream and anything we dream can become a reality.

I never thanked my father for what he did for me and for his family. Similarly, I have never thanked my mother.

My father was not only an intelligent man, he was a creative man who always thought outside the box. When the Vietnamese government made it impossible for the Chinese to maintain a decent standard of living, he was constantly searching for ways to get his family out of the country. My mother and her siblings believe that he deserves over 80% of the credit for the familyʼs move to Canada. The saddest part is, that after all his hard work, he didnʼt have much time to enjoy life in his new country. I do not like to think of him dying. I prefer to think that he has set off alone on another voyage, and is immigrating once again to another strange new world.

I used to start my life story at twelve years old, my age when my father died. I was ashamed of where I came from. Now, I am no longer afraid to admit that I am a VBC (Vietnam Born Chinese).

I am proud of my heritage. I am even prouder of my parents. The decision to leave Vietnam, the only home theyʼd ever known, must have been agonizing for them. The fact that they were leading their family to an uncertain future would have added more stress. I try to imagine what it would be like simply to move to a different country and I cannot. My parents not only had the courage to move to a foreign land but did so knowing it might cost them their lives and the lives of their family. They risked everything to bring their family to Canada. I feel as if I have lived through nothing compared to them.

I returned to Vietnam in October 2007. After this trip, I understand better my parentsʼ determination to leave and create a better life for their children. I caught a glimpse of what our lives would have been like if we had stayed in this undeveloped country

with its pollution, poor sanitary facilities, poverty, and unemployment. Many people have not graduated from primary school, let alone high school. Jobs are scarce and those who are fortunate enough to have work make barely enough money to survive. The average salary is around one hundred US dollars a month for a sixty-hour work week. I saw children forced to work for two meals a day and five dollars a week. The more fortunate played on the streets with hacky-sacks or simple toys. They donʼt ask for more because there isnʼt more to give.

A Note to the Reader

When I began to write about my mother, I realized that her story was part of a larger story, that what happened to our family happened to many Chinese in Vietnam in the 1970s and 80s. A large number, like us, were lucky and escaped to freedom. Many died trying. I have therefore included published news items from various sources (high-lighted in yellow) so the reader will better understand my motherʼs actions and know too that I have not exaggerated details. I have done my best to be factual and relate events as I remember them or as they were told to me. Any mistakes in the text or time sequence are mine.

PART ONE: Vietnam

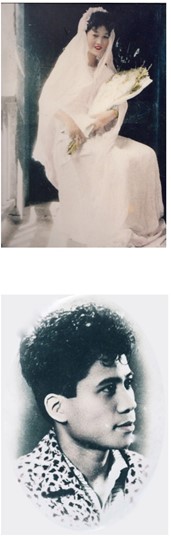

Lan Anh Vuong who has always been called Lana, was born, the second child of ten, on September 14, 1948 during the First Indochina War, in Haiphong, North Vietnam. Although her parents had chosen to immigrate to Vietnam from China for economic reasons, and all their children were born in Vietnam (two died in childhood), my grandparents insisted that they were Chinese and that their children were VBC (Vietnam-born- Chinese). This distinction was important to them. When their children were old enough to marry, they were not allowed to date Vietnamese.

Her parents were strict and instilled old-world values in their children. The girls, without exception, were virgins on their wedding nights. As a child, Lana followed her parentsʼ dictates and dutifully completed elementary school (equivalent to grade five in Canada) but she didnʼt like school, so her father let her leave, at this time, and assist him with his business – buying and selling on the black market. Together, father and daughter would buy such items as salty fish in Vietnam, trade it for rice in China, and then re-sell the rice, at a profit, in Vietnam. (Government restrictions on rice consumption, during the Vietnam war, meant the black market flourished.) As her father also made a living making dentures, the family were so wealthy that his wife never worked a day, outside the home, in her life. Her job was to nurture the children. According to my mother, her kind-hearted and well- educated father was highly respected in their community. It was every young manʼs dream to marry one of his daughters.

When Tung Bun Lee told his mother that he was dating Lana Vuong, his mother didnʼt believe him. She couldnʼt

understand why a pretty, well-mannered girl from a wealthy family would date her poor son. Lana and Bun had been classmates from kindergarten to Grade 5. They used to sit beside each other and, as he was always picking on her, Lana hated him. After she left elementary school, Bun left to work on a boat and soon after vanished. He returned to Haiphong in 1966 and accidentally bumped into his former classmate. He recognized Lana immediately, fell in love on the spot, and asked for her address. As he was a friend-of-sorts, Lana gave him the address, not knowing that he would show up at her house the next morning.

He arrived at her door with gifts. Mom says the little boy, who used to torment her, had grown tall and handsome. He charmed her parents and siblings with his wit, intelligence, and conversation. He charmed her with his sense of humour. By the end of the visit, Lana agreed to date him. She was eighteen years old. He was twenty. “Your father was a great guy,” mom told me recently. “He was polite, had a big heart, and was always willing to help others.”

When he came to the house to take Lana on dates, he always brought gifts of seafood, from the boat on which he worked, for her parents. Even though he was poor, he was generous and more importantly, he was Chinese, so my grandparents thought him an acceptable husband for their daughter. They knew their second child was young and inexperienced and that Bun was the first man to court her, but in those days, a young woman was expected to marry the first man she dated. If she didnʼt, she was considered loose which, in turn, made her parents look bad. Lana did not want to hurt her parentsʼ good name so when Bun asked for her hand in marriage, that same year, 1966, she said yes.

At the beginning of their marriage, the young couple had little money so my fatherʼs mother said the two could live with her for a month. His father had died when he was a child. After three days, my father and mother returned home to see his mother disassembling their bed (a sign that they were being asked to leave.) Both were so hurt, they couldnʼt stop their tears from flowing. My father especially was offended. After they had moved to his wifeʼs parentsʼ house, he would wake up in the middle of night and cry. He did not understand why his mother had rejected him. He felt abandoned.

From the start, the newly-weds wanted to be financially independent. My father began manually making and selling noodles and when he had enough money, he started manufacturing rubber shoes. My mother began a trading business like her father. She would buy and sell everything from simple products like MSG, rice, and condensed sugar, to luxury items like gold, diamonds, silk and foreign currencies. (The only thing that she refused to trade was coffins.) She quickly gained a reputation for being ethical and trustworthy, and so had no problem buying on credit which allowed her to buy in volume and amass a small fortune quickly. My fatherʼs business also thrived. In fact, each were making an equal sum and their joint profits were far greater than the communist government allowed. They decided to do what my grandparents did, hide their paper money behind the brick stove and underground. As often as possible, they converted it to gold.

Even though they were now wealthy, they could not appear wealthy as jealous neighbours might inform the police. When they went grocery shopping, for instance, and bought expensive items such as chicken, meat, or seafood, they had to hide the food at

the bottom of their shopping basket and cover it with cheap vegetables. When they returned home, they had to cook and eat the expensive items secretly. It was not unusual for my parents to spend more on one dayʼs groceries than most people in China or Vietnam made in a month.

Not being able to use their wealth, was especially difficult for my mother. She could not hire a nanny or housekeeper to make her life easier. Although she gave birth to five children over a number of years – Julie born in 1968, Amy in 1970, Eric and Ming in 1973, and Lisa in 1976 – she had to single-handedly look after the children and the home, as well as run her business. My father who held the traditional belief that a man should never do womenʼs work, refused to lift a finger in the house to help her. My mother had to get water from outside, boil it to bathe the babies, feed the babies, and then cook and clean for the entire family.

Only her sister #7 and brother #9 lent a hand which is probably why my siblings and I are especially close to them today.

Mom remembers once when the twin boys got sick, carrying Eric on her back and Ming on her front, and not having a free hand to boil water to clean their dirty bottoms. She didnʼt sleep for three nights straight and when finally, as a last resource she asked my father to help, he refused. “If you ask me one more time, I will go to Ning Hai (a nearby graveyard)”, he yelled. What he was saying, my mother explains, was that if she woke him one more time, he would be dead. She cried throughout the night, thinking: “Are you the only human here? Am I not a human being too? I never ask you to help ever. Is this what I get when, for the first time, I ask you for help?” He had a famous saying that goes something like “If a man does a woman’s job, he will die. If he doesn’t die, he will be poor for life.”

Although mom found dadʼs attitude towards helping her in the home intolerable, she accepted that he was a playboy. She knew he was cheating on her and yet she was too busy with children, housework, and her job to be jealous. “Your father had a high sex drive,” she told me. When he wanted sex and she refused, he would become angry and lose his temper. He beat her twice, in the middle of the night, when she was pregnant with me. It always happened in the dark,” she said, “so he didnʼt know where he was punching.” The second time he beat her, the bruise on her eye was as big as an egg. She was six months pregnant and I was jumping around inside of her and she feared that the next punch would get her in the belly and cause her to abort.

The next morning, she went to her parentsʼ home and told her mother what had happened. Instead of comforting her daughter, my grandmother became angry, and told her that it is embarrassing to hear of middle-of-the-night fights, as fights at that time could mean only one thing: Lana was refusing to have sex with her husband. In no uncertain terms, my grandmother told my mother that it is a wifeʼs job to satisfy her husband.

While my mother was at her parentsʼ home, my father ran away and hid. He knew that her siblings, auntie #1 and uncle #4 would take revenge for what he had done to their sister. When he returned a week later, he begged my mother to forgive him. My mother was chopping vegetables, at the time, and remembers wanting to take the knife and chop him up. She felt that she did not deserve to be beaten, especially since she was six months pregnant with me. This was a turning point in their marriage. My mother hated my father, for some time, and would have divorced him if she could have, but she could not. In the 1960s and 70s

divorce was practically non-existent in China and Vietnam. Married couples didnʼt want to hurt their children or lose face with their parents. She felt that she had no choice but to accept that her marriage followed the same traditional rules as her parentsʼ marriage. She wasnʼt happy but she remained.

At times, her marriage seemed the least of her worries.

Before her first child was born, the US involvement in the Vietnam War had escalated and too many American B-52s were dropping bombs over the north. By the time I was born, Hanoi and Haiphong were targeted and bombed over 2000 times. Schools, hospitals, and whole residential blocks were destroyed. My mother remembers running, trying to get away from planes flying overhead and the bombs that were exploding all around her. She didnʼt know which way to run. Helpless, she dropped to her knees and begged the planes to spare her life.

Before my twin brothers were born in 1973 (the older boy died at 3 years of pneumonia), the Americans had withdrawn from the war. There were no more B-52s overhead but foot soldiers from North and South Vietnam continued to fight and kill innocent civilians. Finally, in April 1975 South Vietnam surrendered to the North and the country was united but not in spirit. The new “peace” created many problems for my parents.

| The political and economic turmoil that followed in 1975 intentionally set about to remove the wealth and class structure created by the Chinese community in Vietnam. The removal of goods and wealth was meant to level the playing field and remove class distinctions. The communityʼs values of education and preparedness would soon allow them a means of exit, and a means of viability elsewhere in the world. It was this hope of renewed viability abroad that led them to leave. With little else to lose from their region, the ethnic Chinese-Vietnamese began an exodus in search of the freedom they once enjoyed. 1 |

Due to our wealth, status, and ethnicity, my family were directly affected by the reforms of the new unified Vietnam. I say “my family” but all Chinese Vietnamese were forced to conform to new laws – laws that would take away their wealth and freedom. My parents were most upset about the law that required all Chinese to give up their Chinese citizenship and become Vietnamese citizens. They did not want to be citizens of a country where their children would be forced to do military duty.

New currency reforms also affected their standard of living. They did not want to raise their children in a third-world country where they could not buy fresh water, and enjoy fresh air and freedom of speech. Two years after the unification of north and south Vietnam, my parents decided to leave. Fortunately, they had prepared by converting their paper money into gold and, as I mentioned earlier, hidden it from the authorities. My mother says that she remembers three occasions when paper currency was devalued overnight to the point of being worthless. By the end of the war, my parents had stockpiled enough to pay for the familyʼs escape.

| In late 1977, ethnic Chinese in northern Vietnam began crossing into southern China, driven partially by rumors of impending war between Vietnam and China. The rumors suggested that Vietnamʼs invasion of Kampuchea would prompt a military response by Kampucheaʼs close ally and supporter, China. Vietnam suspected Chinaʼs hand in the rumors, and also questioned ethnic Chinese loyalties in the north. In the last three months of 1977, ethnic Chinese in the North were put under surveillance, expelled from the Vietnamese Communist Party, and forbidden from speaking Chinese in public.In addition, thousands living in the five Vietnamese provinces bordering China were moved away from the area as “security risks.” 2 |

PART TWO: In Transit as Refugees

| As early as Feb. 1978, the on-off border between China and VN in the North had begun to affect the lives of Chinese communities strung along the common border as well as in the Hanoi-Haiphong area. As thousands of ethnic Chinese streamed across the border into China, the Chinese government accused the Vietnamese of systematically and forcibly driving the Chinese out of Vietnam…. It was clear that Vietnam authorities were making life difficult for the Chinese in Vietnam. [Their] political loyalty was suspect, whether they were Vietnamese citizens or not and many ethnic Chinese were dismissed from their jobs and subjected to frequent security checks. 3 |

In May 1978, my mother and father, four children, and four of my motherʼs siblings sadly said goodbye to our neighbours, knowing that weʼd probably never see them again, left home (openly and legally), and caught a train to Liangshan which is within walking distance from the Vietnam/China border. Here, Chinese soldiers welcomed us with open arms. (A year later this would not have happened but we were among the first Chinese to escape Vietnam, and the government of China still considered us citizens returning to our homeland. The total number of ethnic Chinese leaving Vietnam by land and sea to September 1979 was between 432,000 and 466,000 people, although significant numbers continued to flee well into 1980.) When we reached the actual border, we were once again welcomed by friendly Chinese soldiers who drove us to our new home.

Although we were supposedly “home”, we did not have a say in where we would live. The soldiers drove. We sat, waiting to find out where. Our destination was to be a surprise. My parents were hoping to live in an urban environment and work in a factory. Unfortunately, we were driven to a farming area in the village of Tian Xi and given one of the small bamboo huts for families (around 250 sq ft), furnished with bamboo bed frames and tatami for mattresses. The kitchen was outside and shared with many other families. The washroom, also public, was located several blocks away.

While my father was lucky and ran back and forth between Vietnam and China trading goods, my mother and her siblings were forced to work in jute fields, harvesting the plants which meant cutting each stalk close to the ground. The work was back- breaking and the sharp ends of the plants scratched and scrapped their arms and legs. When the jute season was over, they had to work in rice fields. Every worker was assigned an area of a field and expected to complete the work. My mother and aunties were scared of the disgusting muddy earth that was full of worms and cow and dog feces. They hated it more when the weather was wet and their feet got stuck in the mud. Every morning a government worker would come to the hut and call out mom and auntiesʼ names. Often I would say that they were sick. In the beginning, this was acceptable but after too many sick days, the authorities asked for a doctorʼs note.

Every day that they worked, mom and aunties shed many tears, thinking how much easier life had been in Vietnam where they had been entrepreneurs and made much money. On the farm, the monthly salary was 27.50 RMB – only enough for my mother to shop on Sunday. This made the work more difficult

because the family didnʼt need the money but my mother was afraid, if she refused to work, weʼd be sent back to Vietnam.

While she and her sisters worked in the fields during the day and looked after the children at night, my father was making a great deal of money. Thanks to letters from friends who had left Vietnam before us, he knew what was sellable in China (motorcycles, gold, watches, hi-fi stereos, records, and silk scarves.) His earnings plus the gold my parents had brought with them allowed us to eat better than most in our community but unfortunately, my father could do nothing about the living and working conditions. My mother kept begging him to find a way to get the family out as soon as possible. She told him that she would rather die in transit than live as a farmer for the rest of her life nor could she stand the thought of her children growing up in such a place and becoming farmers. After she was stung by a bee in the field (luckily, uncle #7 was there and told her to lie down), she was even more insistent that they leave.

Nine long months later, my father finally made a connection and was able to buy a sailboat for 9000 RMB (which was a lot of money as most people in China were making only 27.50 RMB a month) and my parents secretly prepared to leave.

We took the 90-minute train ride to Nan Ning and then an hour bus-ride to Bei Hai, a harbour town, where our sailboat was docked. My mother was under no illusion that it would be an easy journey. Letters from friends had informed my parents about the perils of traveling by sea. By all reports, many boats had sunk and many people had drowned. Other boats had been attacked by pirates who robbed and raped the passengers. Mom said that she would rather risk death for her entire family in the open water than remain in China. She had expected sanitary conditions in her homeland to be at least as clean as what she was used to in Vietnam but the living conditions in Tian Xi were much worse. If the family could only get to Hong Kong, my mother believed, the United Nations would help us find our way to a developed country. (She had heard about the United Nations assisting refugees through secret wire-tapping into radio news programs.) My parents were willing to risk everything for such an opportunity.

| Following the communist takeovers in Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos in 1975, about three million people attempted to escape in the subsequent decades. With massive influx of refugees daily, the resources of the receiving countries were severely strained. The plight of the boat people became an international humanitarian crisis. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) set up refugee camps in neighboring countries to process the boat people. The budget of the UNHCR increased from $80 million in 1975 to $500 million in 1980. Partly for its work in Indochina, the UNHCR was awarded the 1981 Nobel Peace Prize. 4 |

Saying goodbye to my grandparents was difficult for us all. We had no idea if weʼd ever see them again. Two of my motherʼs brothers remained to take care of them: if anything happened to us, they wouldnʼt be left childless. Auntie #1 and her family also stayed behind – not to take care of the parents – but to see if we arrived safely, before they followed.

And so my family secretly left Bei Hai on the sailboat that was to take us to Hong Kong. The boat, approximately 50 ft long by 12 ft wide, was to carry my family, my motherʼs siblings, a captain to sail the boat, and his immediate family. In lieu of payment, my parents told the captain that his family could travel free.

He was not an honourable man. He brought not only his family on board but a number of strangers – anyone who could pay him two ounces of gold for a seat. Instead of a spacious ride, there were fifty-four people on the boat, leaving hardly enough room to sit down. The trip took around a week, though in my childʼs mind, it seemed like a month. On the rough and choppy South China Sea, the boat rocked violently, upsetting most of the passengers. People were vomiting from one end of the boat to the other. The only thing we managed to eat all week was congee.

My family sat huddled together, holding onto each other. All we could see was endless waves rising and falling, rising and falling. I was mesmerized until we hit a storm and the waves rose to over twelve feet in height. Suddenly, a boat ahead of us flipped upside down and disappeared. A little later, dead bodies floated past us. I was so scared, wondering if we would be the next ones to flip over and die. Looking back, I can only imagine how anxious my parents must have been, at that moment, knowing our boat was too small to outlive such a storm. As every big boat approached, everyone in the boat frantically waved for help.

Finally a large fishing boat came to our rescue but the captain, seeing an opportunity to profit, demanded all the gold necklaces, bracelets, and rings that we were wearing as payment for his help. No one wanted to risk going through another storm, so everyone on the boat took off their jewelry and handed it to him. Only then did he agree to tow us to Hong Kong.

A day later, we saw the bright lights of Hong Kong appear before our eyes. We felt as if we were arriving in heaven. Auntie #7 (Annie) remembers that we were boat #310 to dock. As soon as we stepped off the boat, we were sprayed down with disinfectant and taken to the “dark warehouse”. At first, we were so happy to be alive that nothing bothered us. After a week, we were taken to Kai Tak East Refugee camp which was surrounded by chain-mail fencing, topped with rolls of barbed wire. Neither the warehouse nor the camp had beds. Twelve of us (my family and aunts and uncles) slept huddled together on around 300 sq ft of floor space. (We did not sleep on bunk beds until we were taken to the Argyle Refugee camp, where people who had approved sponsorships were moved, before leaving Hong Kong. Here we would also receive “manner” training and medical checkups.)

The living conditions in Kai Tak East camp were less than ideal. Reportedly the camp could hold up to 10,000 refugees but even I could see with my young eyes that there was not enough space or facilities for so many families. All the electrical outlets, for instance, were lined up along a simple long countertop. Every day, I would wake between three and five a.m. to stand in line to reserve a plug so when my mother woke up, she could boil water with which to cook. The breaker was constantly snapping from overuse. To supplement our diet, distant relatives, released before us, threw snacks and instant noodles over the fence. We would quickly put the food into a pail that my father had tied a rope to. If we had been caught with such supplies, my father would have punished by security guards so, instead of taking the stairs, he carefully pulled the pail up the outside of the building to the second floor where we lived. Once he was caught and put in solitary confinement – a jail within a jail.

When we first arrived, the security forces within the camp were nice to us but as more and more people arrived, they became mean and abusive, especially to women, children, and the elderly. Mom witnessed a guard throwing sand into a seniorʼs bowl of noodles. We thought of the security forces as “prison guards” which they were in the sense that all carried a short stick and beat whoever displeased them, whenever they chose.

Sometimes the men would retaliate and fight the guards. Or battles would break out between people from north and south Vietnam, or between the Chinese and Vietnamese.

Once a guard tried to molest me and said that if I told my parents, I would be in big trouble. I was too scared to tell. I thought if I did, my father – a big man with a martial arts background – would beat up the guard, even kill him, and then he would be in jail forever. (I have hated Hong Kong for most of my life because of my experiences here.)

| The plight of the boat people became an international humanitarian crisis. There were untold miseries, rapes and murders on the South China Sea committed by Thai pirates who preyed on the refugees who had sold all their possessions and carried gold with them on the trips. The UNHCR, under the auspices of the United Nations, set up refugee camps in neighbouring countries to process the “boat people”…. According to stories told by the Vietnamese refugees, the conditions at the camps were poor. The women and children were raped and beaten. Very little of the money donated primarily by the United States actually got to the refugees. 5 |

I understand now that the security forces within the prison must have been envious of the refugees and angry at the UN for helping us. We could go to the country of our choice, whether we were rich or poor, skilled or unskilled. They would never have this option. Soon after our arrival in Hong Kong, my parents had had to decide to which country they would seek asylum. My father wanted to go to Canada because a distant uncle who was a sailor had told him that Vancouver was the best place to live and raise children. My mother wanted to go to the United States. She still hadnʼt forgiven my father for beating her and thought this would be the perfect time to separate. Dad begged her to come to Canada with him. He said heʼd heard that if he worked full time, heʼd make enough to support the whole family so she could stay at home with the children. He even asked his friends and her siblings to help convince her that her place was with him. Finally she relented and agreed to seek sponsorship with him in Canada.

As soon as we heard that the congregation of the Olivet Baptist Church in New Westminster were sponsoring us, we were moved to Argyle Refugee Camp and my parents were allowed outside of the camp to work. They spent their remaining gold – except their childrenʼs wedding jewelry – to buy food, clothes, a television, and a camera to bring with us to Canada.

In total, we were in Hong Kong for ten months.

| During the late 1970s, Canada admitted nearly 70,000 refugees from oppressively communist rule in Vietnam. These people were often dubbed “Vietnamese boat people” because of their willingness to flee the country and taking to the ocean in tiny, leaky, unsafe boats. Many Canadians agreed to sponsor such refugees under new changes to the Immigration Act, 1976, which created a “refugee” class. 6 |

PART THREE: Life in a Foreign Land

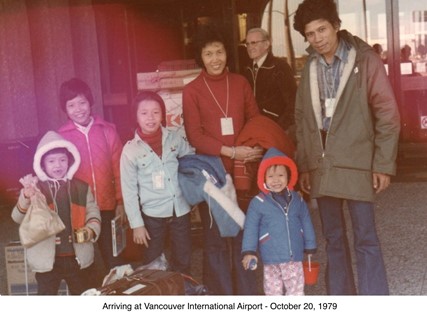

On October 13, 1979, we left Hong Kong and flew to Canada. Instead of feeling elated that we were finally on our way to freedom, our feelings were mixed. We were worried about reports weʼd heard from friends of friends who said Canada is a freezing country without rice, where people only eat whole-wheat bread. During the plane ride, we went from happy to scared to excited to nervous, and back to happy. Although our final destination was Vancouver, all refugees had to stop in Edmonton for an orientation. As soon as we got off the airplane, we were met by local authorities and driven to a military base where we were sprayed, from head to toe, with a stinky disinfectant and given a medical examination. The thing that scared us all, my mother says, was the below zero temperature. Coming from a tropical country, we had never experienced such freezing weather, nor had we ever walked in snow up to our knees. Before leaving the base, everyone was given ten dollars by a bank to open our first Canadian bank accounts.

One week later – on October 20th, 1979, – we flew into Vancouver where Betty and Frank Mackenzie, members of the Olivet Baptist Church congregation, were to meet us. Although we knew what they looked like as weʼd received their photograph In Hong Kong, they had no idea what we looked like. They knew only that they were collecting a family of six. We must have looked as lost as we felt, standing, searching the faces in the crowd, with all that we owned at our feet – one small and one large suitcase, and a television and a camera. The only items of value were the four 24K gold necklaces, bracelets, and rings for the childrenʼs weddings. An interpreter from the immigration department waited with us. When everyone from the plane had been picked up, we

became scared, thinking that the Mackenzies werenʼt coming. At last, they appeared.

I do not know how the Mackenzies communicated with my parents who spoke next to no English – most likely with smiles and hand gestures (after the interpreter had left.) Frank drove us to the home of Velma and Lorne Hilton who had volunteered to put us up in their basement for a week until the three-bedroom apartment at 12th Avenue in Burnaby was ready for us. Both couples

impressed us with their kindness but Betty and Frank became our guardian angels. They were immigrants themselves, from Scotland, and by the time we arrived, Frank had already retired. Betty, who was nine years younger than her husband, worked part-time as a secretary for the Olivet Baptist Church.

When we moved into our new home, a week later, we were happy to learn that the Mackenziesʼ home was only several blocks away. We were also happy, after not having had a proper home for two years, to find ourselves in a private three-bedroom apartment that the congregation of the Olivet church had thoughtfully furnished with everything that they thought weʼd need, including furniture, bedding, dishes, cutlery, and pots and pans. Even the fridge was full of food. Although, nothing was new – everything had been donated by the congregation – my parents were left speechless by the generosity of these strangers. Most parents, my mother said, would not have done as much for their own children.

When we first arrived, the Mackenzies were with us every day “You werenʼt scared,” speaking of the family in general, Betty remembers. “You were shy and feeling your way around.

Everything was new to you.” Frank and she helped my father and mother with everything from enrolling the children in school to taking us to dentist & doctor appointments to eventually helping my father find a job. They introduced us to McDonalds restaurant and our first picnics. They practiced English with us every day for a year. (I became the translator for the family as I picked up the language the fastest. Dad also was a fast learner.) After I started school, I would telephone Betty, at least five days a week, whenever I had a problem with homework or was worried about something. As each day passed, we felt closer to the Mackenzies. My parents began calling them mom and dad, and we children called them grandma and grandpa. Betty and Frank didnʼt mind as they felt the same about us. We were their children and grandchildren.

Even though the Mackenzies were more than generous with their time – time volunteered freely with no financial gain – the first year was difficult for everyone in my family but my parents suffered more than we children. Although mom was thirty- one and dad was thirty-three, they must have felt like children themselves. They couldnʼt speak the language. They couldnʼt read road signs or food labels. They didnʼt understand the school or health system. Everything was foreign. In a letter to the Olivet Baptist Church and the Mackenzies, written two years after our arrival, my father describes this time as “a nightmare” and says the family is “ashamed that we made lots of trouble” for their sponsors, especially the Mackenzies. He thanks Betty and Frank who “looked after us (from young to old) with great care, including clothing, living, learning and job…” and notes that the Mackenzies “werenʼt afraid of difficulty, spending time to help us grow up.”

(Is it any wonder that 32 years later, we still call Betty Mackenzie “grandma” and love her dearly? Sadly after 55 years of marriage, Frank died of cancer in 1995.)

| In the initial period, the refugees will be confronted by the reality of what has been lost. From a high occupational and social status at home they will plunge downward in their new land – from professional to menial, from elite to an impoverished minority…. To the stresses and traumas inflicted on refugees before escape, during flight, and in refugee camps, one must add the difficulties and fears that face the refugees during resettlement. Acculturation, loss of status, identity confusion, language difficulties, poverty, concern for separated or lost family members, guilt, isolation, host hostility, and countless other factors add to the pressures on the refugee in a strange land. 7 |

We still feel indebted to Betty and Frank Mackenzie, Velma and Lorne Hilton, and the whole congregation of the Olivet Baptist Church who besides helping with numerous practical matters, paid the rent on our apartment and gave us a living allowance of sixty dollars a week for a year so my parents could attend ESL classes. (We are also grateful to the UN and the Canadian government for their assistance in bringing us to Canada. We slowly repaid, by installment, the money the government paid for our airfares.)

As the sixty-dollar living allowance had to pay for all groceries, toiletries, bus fares and clothing, my parents had to watch every cent they spent. When we needed clothes, we bought second-hand at Thrifty where we paid twenty-five cents per item for a pair of pants or a shirt, or a skirt, or a sweater. My mother, who never had had to worry about money in Vietnam, learned to

be frugal when grocery shopping, buying in stores like Safeway or SuperValu where she could get bags of apples or oranges that were beginning to rot for fifty cents a bag. By cutting out the good part, she was able to feed her children fruit. Instead of buying meat or poultry, she bought pork or chicken bones and would cut off the little meat that was on them for spring rolls and other dishes. She settled for broken rice, instead of regular rice because, at that time, broken rice cost half the price of whole ($8 for a 50 lb bag). Today, ironically, regular rice is cheaper.

Even though we were on a tight budget, mom and dad had no complaints about the way they were being treated. They were more than grateful. They were astonished that complete strangers had given the family so much and expected nothing in return. My father changed when he came to Canada, my mother says.

Before, he never helped with the housework, insisting it was womenʼs work. In Canada, he would take the bus with mom to Chinatown to do grocery shopping. He helped with babysitting too.

I still remember how difficult and scary that time was. I didnʼt dare go into shops as I knew my family could afford only the essentials like groceries. Still, I couldnʼt help wanting toys like other children although I didnʼt tell my parents. Years later, my mother told me that she found it difficult too. Sometimes she felt that the learning curve was too steep, that she would never find her way in this new place, but these were momentary lapses. Once my mother sets her mind to something, she doesnʼt give up.

I donʼt want to give the wrong impression. I was grateful. The whole family was grateful that we had survived. After the ordeals in Vietnam, China, and Hong Kong, we sometimes felt as if we were reborn in heaven. In his letter of November 1981, my

father expressed his gratitude. Although his English isnʼt perfect, I am amazed that he wrote so well, after only two years in Canada. He sounds like a poet. “Words canʼt express our feeling for your graceful love and support… The little kids, now they grow up healthily, happily and independently. They are under your patient teaching and love. In response gratitude. we promise to work harder and harder to create a happy sweet home and a brightful future with our own hands and wisdom.” This letter meant a lot to Betty. When I told her I was writing a book about my mother, she sent me a copy of the letter. The original is in the church archive.

After a year of ESL lessons, the church helped my father find work. Although the minimum wage at the time was $3.25/hour, my father earned $12.50/hour at a steel factory which meant that my mother did not have to work. This made them both happy.

Their happiness lasted for a few short months. My dad began throwing up blood and discovered a lump on his neck. By some strange coincidence, his sister-in-law, Annie (Auntie #7) also found a lump on her neck. They went together to see Dr. Lee. Annie was told that her lump could be removed and she would be fine. My father was told that he had nasal-cavity cancer that was so advanced there was little the medical profession could do for him.

Dr. Lee did try to arrest the cancer with a series of radiation treatments, but my father, though he believed in traditional medicine, was not willing to put all his faith in it. He wasnʼt ready to die and so began searching in earnest for alternative medicines to save his life. He fought to the end, trying everything that anyone suggested from special shots from Japan to herbs from China to regular martial arts practice. If he could not find a cure, he was willing to settle on anything that might prolong his life.

With my dad too ill to work, my mother had to find a job to support the family. Grandma and Grandpa Mackenzie helped. While Frank drove my father to the hospital for treatments, Betty searched in a local newspaper for a job for my mother. She found one at Hawaiian Village, a restaurant advertising for a “kitchen helper”, for someone willing to work a six-day-week for $675 a month. The duties included helping the head chef with food preparation, assisting him with some cooking, as well as mopping floors, gardening, and cleaning toilets. My mother who had come from an affluent family and had run her own business must have found taking such a job demeaning. I am not surprised that she was especially disgusted when she had to clean the menʼs washroom as drunks vomited and urinated on the floor on a regular basis.

Although she hated the work, she had little choice but to accept it. She had thought when she arrived in Canada that it would be the beginning of a new life. She had thought sheʼd feel as if sheʼd been reborn in heaven but, after one year, she felt as if she were in hell. Her husband was diagnosed with cancer. Her father was also diagnosed with cancer. She was working at a job she hated. She thought that things couldnʼt get worse and then she discovered she was pregnant.

She had never had an easy time when pregnant and unfortunately, this pregnancy was worse. Whenever she smelt the steam from the rice cooker in the restaurant, she would double over and vomit continuously until her stomach was empty. Her boss told her that she had a choice of either keeping her baby or keeping her job. She decided the job was more important as she had four live children who she had to feed. Life was hard enough. She couldnʼt afford another child. She asked Grandma Betty to drive her to the abortion clinic, without consulting her husband, and terminated her pregnancy on the same day in 1980 that her parents arrived in Canada.

My father was furious when he found out that his wife had had an abortion, behind his back, without his consent. A fortune teller had told him, years earlier, not to have any more children after his youngest, Lisa was born but if his wife became pregnant accidentally, they must keep the baby or he would suffer bad karma. Not long after the abortion, my father found out that his cancer was incurable. The fortune-tellerʼs prophesy had come true, he insisted, and it was his wifeʼs fault. His cancer might have been cured, if it werenʼt for the abortion. To this day, mom feels bad about making the decision by herself to abort.

To add to my motherʼs problems, the head chef at Hawaiian Village was rude and inconsiderate. He was also secretive. He thought if no one knew the recipes for the restaurantʼs special sauces, he couldnʼt be fired. Mom was smarter than he was. She watched as he cooked the food and sauces on the open stove so she knew how to cook them. The only thing she didnʼt know was how-much-of-what went into the sauces. She was determined to find out. When she saw the sauce bucket was getting low, she would watch the chef closely, and then peep to see how much of what ingredient he was adding to the bucket. She would memorize as much as she could and then go to the washroom and write it down on a piece of paper and hide the paper in her sock. It wasnʼt long before mom had the full recipe of every sauce and dish in the restaurant.

The next time, the chef had a fight with John, the owner of the restaurant, mom assured her boss that she knew every recipe and felt confident that she could take over the position of head chef. John fired the man and promoted my mother which meant her salary increased from $675 (minimum wage) to $1300 a month. Although she was happy to finally be making a decent wage, she was happier still that she no longer had to garden, vacuum, and clean the disgusting toilets.

She continued as head chef at Hawaiian Village until Mr. Kim a customer at the restaurant, contacted her and asked if she would help him open a Japanese restaurant. As he promised her $1500 a month plus 50% of the house tips, meaning her salary would be over $3000 a month, she could not refuse. The only problem was that Kinja Gardens Japanese Restaurant was in White Rock and traveling from East Vancouver by public transit – a ninety-minute bus ride – seven nights a week, as well as looking after her family and sick husband, exhausted her.

Although I have no memory of this, my mother says that when I was ten years old, I would ride on my little tricycle to the bus stop at eleven p.m. – three blocks away from our home on 13th Avenue – to meet her returning from work because I knew that she was afraid of walking home alone in the dark. Two years later, when the family moved to Turner Street, I would sit at the front window with the outside lights turned on so she wouldnʼt trip on the front steps. I was there every night and refused to go to bed until I knew she was home. Mom says that she can still picture me in the window waiting for her and, since that time, never doubted my love for her.

I cannot remember the exact sequence of events in the years when my mother started working and my father was fighting for his life. I do know that it was an especially difficult time for

mom as her father who was only sixty-one died of cancer, six months before my father. Mom adored her father. He was a kind- hearted man who never laid a hand on his children even when they misbehaved. He preferred to teach by example and always treated them with love and compassion. Although married over forty-years, he never once fought with his wife. Their marriage had been arranged by their respective families and so, as tradition dictated, they met for the first time on their wedding day.

Though grandpa was well-educated, his bride came from a poor village and could neither read nor write. At that time, parents didnʼt send their female children to school. They felt that there was little reason to educate females as they would eventually marry and become somebody elseʼs responsibility. My grandmother couldnʼt even read numbers. She stayed at home and helped take care of her brothers and the housework and farm work. When she married, she looked after her own home and children. She, like her husband, was a kind-hearted parent though she did tend to nag the children. Still, they adored her. My mother was especially close to her, and after my father died, they became even closer.

I remember my father, towards the end, lying in bed, thin and emaciated, his body bruised and aching from the radiation treatments. I still cry when I think of his suffering and the conversations we shared. “I donʼt dare wish for a long life,” he said, “ I just want to stay alive long enough to witness my children growing up.” When he was close to death, he said he had one regret. In keeping with an old Chinese custom that says a father must leave his male heirs a home, he had dreamt of buying his only son a motor home. At that time, a motor home cost around $20,000. Having

enough money to buy his boy a real house was beyond his imagination.

(My mother wants to fulfill her husbandʼs dream of leaving their only son a home and so she refuses to sell her nicest house in Vancouver and has bequeathed it to her son in her will. She made sure that all her daughters know the reason why Eric will inherit the house so we wonʼt be jealous and feel that he is being favoured. My sisters and I understand and respect momʼs decision. Moreover, we are happy that dadʼs wish will be realized.)

Three years after arriving in Canada, my father, Tung Bun Lee died at the age of 36, in the Royal Columbian Hospital in Burnaby. (I’ve missed him at every milestone of my life so far: high school graduation, my wedding day, the day I became a mother.)

My mother did not have the money for a proper burial. She would have liked to bury her husband in a beautiful coffin that would then be preserved in a cement box but she didnʼt have the money for the coffin, let alone the five hundred dollars to pay for the cement box. In the end, the government supplied a simple wooden casket. Mom paid for the humblest burial space in the cemetery at the bottom of a hill where the water drains. To this day, she feels sad that she didnʼt have the money for the cement box. She cannot bear to imagine how quickly the coffin would have disintegrated in the damp earth.

We held a traditional Chinese burial service at the cemetery for my father. My mother, sisters, aunts, and I wore customary clothes with a white hood on our heads. My brother wore a white shirt and white headband. As is the sonʼs role, my brother, carrying a picture of our father and a sign with his name, walked in front of the coffin to the open grave. When the service at the graveside was over, my family continued to mourn for my father for forty-nine days (another Chinese custom.) On the seventh day, my family sat in the living room with dadʼs picture on a display shelf, waiting for his soul to return. Incense, which is food for the dead, was burned. We believe that dad would come back to check on us and so we talked to his picture, believing he could hear what we were saying. Every seven days, we would repeat this ritual until forty-nine days have passed.

My fatherʼs mother came from Winnipeg for the funeral and, before the third seventh-day (twenty-one days later), she insisted that she had to return home to look after her younger sonʼs two children. My mother was deeply hurt. She did not understand how her mother-in-law could be so disrespectful and leave before the forty-nine days of mourning ended. “Even though your son died,” she said to herself, “you have four grandchildren who are still alive who will continue to carry the Lee surname.”

She knew her mother-in-law favoured my fatherʼs younger brother, but still she was hurt by my grandmotherʼs choice. This didnʼt stop her from telephoning my grandmother weekly and sending her money yearly. “It doesnʼt matter what others choose to do,” she said, “we must behave well. As daughter-in-law and grandchildren, we must always show respect to your grandmother because, without her, your father would not have existed nor would you.” Furthermore, mom insisted that we show respect to all seniors, no matter who they are, even if they upset us: “They are older and have less time left on this earth,” she told us. “Try to give in to them as they could leave us at anytime. You guys will grow old someday too. What goes around, comes around. Besides, you donʼt want to have any regrets when they are gone.” My mother practiced what she preached and was always respectful to her parents, mother-in-law, and those older than herself, and although she didnʼt always agree with her husband, she always treated him with the respect he was due as a husband and father of her children.

Betty Mackenzie remembers my father as being a kind- hearted man who loved his family and was always protective of us. He never failed to show his gratitude to Frank and Betty. On Motherʼs Day, May 1982, he took Betty to lunch and told her that sheʼd been such a great mother to him that he wanted to say thank you. This was the last lunch they shared.

PART FOUR: Mother Alone

After my father died, my mother struggled to make ends meet. A widow at thirty-four with four children, aged six to fourteen, she qualified for welfare but refused to apply. She knew that welfare would have provided enough to keep her family going but she wanted more than enough for her children, and so she continued to work at Kinja Gardens seven nights a week. She remembers, during that first winter after my father died, her mother getting angry at her because she was wearing a red sweater. In Chinese culture, red is a colour for celebration. How could she wear red, her mother demanded, when her husband had just died? She was sorry that she had annoyed her mother, mom told me, but she hadnʼt even thought of the colour she was wearing. She wore the sweater because it was the warmest one she had found in the twenty-five-cent used-clothing bin at the Thrifty store. She couldnʼt afford to be sick and miss work with so many mouths to feed.

The only benefit from the government that she agreed to accept was social housing as the rent, based on a percentage of a personʼs income, was more affordable. Unfortunately, social housing is not always in the best area and our house at Cassiar and 6th Avenue in Vancouver East was no exception. Most of our neighbors were on welfare. Many were drug addicts or prostitutes or both. There was a lot of child abuse, fights, and noisy parties. At twelve, I saw people with needles – using them and then tossing them on the ground. This frightened me more than the rats that ran around our ugly townhouse. As she worked at night, my mother had no idea of what went on in the neighborhood, and I didnʼt want to upset her so I didnʼt tell. (At 16, I married a man fifteen years older than me to escape the squalor.)

She worked hard at Kinja Gardens Japanese Restaurant, and before long, customers were lining up outside the restaurant from five to ten pm every evening. Although Mr. Kim, her boss, was normally very kind, he would become stressed when the restaurant was overly busy, and lose his temper. The big problem, my mom says, is that the restaurant was under-staffed. She had only one helper in the kitchen and when her boss lost his temper, she would return home more exhausted than usual. Life often felt like a nightmare. She slept less than six hours a night, and when her teenage daughters were out late, she worried and often cried herself to sleep. More than a few times, she asked herself if staying single for her childrenʼs sake was worth the anguish.

When she began working for Mr. Kim, he would drive her home at night. After she had worked for him for some time, he drove her only to the bus stop. Later, he didnʼt even do this. Mom had to walk, in her fabric shoes, even if the ground was thick with snow, up a high hill in the dark to catch her bus. If she missed the bus, she would have to wait an hour for the next one. This was especially difficult in winter in the freezing cold. There were times when she saw the bus on the hilltop but she had no energy, after working non-stop for so many hours, to chase after it. Once, when she attempted to run and catch it, she slipped and fell, and although she was sure the driver saw her, he didnʼt stop.

She was so upset that her eyes welled up with tears and she asked herself, “Why should I be alone in the world. Why canʼt I be dead like my husband? Why do I have to be a single mother with so much stress? Wouldnʼt it be easier to jump off this cliff and end my life now?” And then images of her four young children popped into her head and she knew she had to continue, that she had to be strong, if not for herself, for them. They had already lost one parent. What would their lives be like, if they lost two? She could not bear thinking about that. She needed to raise them, provide for them, and watch them grow up. She must be successful as she had brought them into the world. There was no way she could abandon them. She remembered a Chinese saying that her father had told her: “If you can swallow your pride one hundred times, then all will turn into gold someday.”

Within two years, Kinja Gardens was so successful that her employer decided to open a second location in North Delta. He soon found that two restaurants were too much for him, and offered to sell the second to my mother for $110,000 with no money down, zero percent interest, as a way of thanking her for the success of his business. My mother, not a stranger to risk, agreed to buy the North Delta restaurant without knowing if the location would pay for itself.

As well as being an excellent chef, she proved herself to be a resourceful business woman. Until she bought the restaurant, it had only been open for dinner. When it was hers, she opened for lunch as well so she would be debt-free sooner. Fortunately, her brother #9, Andy was able to help manage the front of the restaurant. They agreed that when her children were old enough to take over, he would leave and pursue his own career. At first, Julie and I worked as bus-girls and slowly learnt how to wait on tables. My brother Eric, at eleven, stood on a stool to operate the dishwashing machine. Lisa, at eight, helped with sushi rice preparation. One by one, we were promoted. Three years later, my mother paid off her debt in full and decided to once again open only in the evening.

At this time, my older sister was old enough to manage the restaurant so Uncle Andy left to become a realtor. The restaurant was truly a family business. As well as our immediate family, my mother hired some of her siblings and my cousins and, although we all worked hard, we did have some fun moments. For instance, and this happened later, if one of us was dating, that person would bring the date to the restaurant to help out, usually on busy evenings. When the evening ended, the family would discuss the dateʼs work, analyzing how bright or quick the person was, and then collectively decide whether or not the family member should continue dating that person. This was all done in the spirit of fun and no one really took the collective decision seriously.

As the debt was paid and the restaurant continued to do well, my motherʼs saving account kept growing. When she had saved $40,000, she bought her first building lot in Surrey. After building on the lot, she sold it for a profit of more than $120,000. She bought more lots and built more houses in Surrey. When she had saved enough again, she started buying in Vancouverʼs East side. Thanks to the real estate market in the 1980s that kept getting stronger and stronger, and my motherʼs determination not to miss any opportunity to make her share, she went from being a poor widow to becoming a self-made millionaire. All in all, it took her only eight years. When she fully retired at sixty years, she had been involved in buying and selling a total of fifty-four houses – some new construction, some renovation, and some quick flips.

I am still astonished at her courage though I know it wasnʼt easy. The worst setback happened when she hired an Italian builder to build a house on her property. Before the framing was complete, he disappeared with $30,000 of her money. At first, she couldnʼt believe that someone would do such a thing. Sheʼd go to the construction site and wait for him. When he didnʼt show up, she would telephone him. When he didnʼt answer, she would sit down and cry, praying that heʼd appear. After awhile, she had to accept that he was gone. By this time, the sub-trades had put liens on her building. She knew nothing about the construction procedure and worse, she could not speak English well enough to ask questions. She began driving around to nearby construction sites, looking for Chinese builders who might help her. Finally, she found several and, in tears, told them her story. The builders, feeling sorry for her, guided her step-by-step until her house was complete.

In the process, she became acquainted with the housing inspectors who, after hearing her story, were generous in their assessments. To thank them, she gave them business cards, inviting them to eat at her restaurant which earned their respect and made her new life as a builder easier. She still doesnʼt know where she found the guts to do what she did. After completing the first building, she felt confident that she could take on more building projects, including helping her siblings to build their first houses in Vancouver.

I think my mother pushed herself to make more and more money because she wanted the best for her family, especially her children. We had lost one parent. She didnʼt want us to suffer any more losses. She also didnʼt want us to work for a fixed salary and not have the resources to enjoy the freedoms that our new country offered so she worked all the time, praying that she would stay healthy. During the day, sheʼd be on construction sites. In the evening, sheʼd be at the restaurant. After eating breakfast, she did not have the time to eat a real meal again until the dinner rush was over at the restaurant. Typically, this was around ten at night.

As momʼs interests switched from the restaurant to real estate so did her childrenʼs. When she needed help understanding building jargon, we translated for her. When she had to communicate with some person in the building trade or at a financial institution, we became her voice. Before long, we were all fluent in the language of construction and development, real estate and speculation, which gave us the tools to make our own fortunes.

When mom became her own builder, she chose to build designs by her seventeen-year-old son who had been winning design awards since high school. Although most mothers think their children talented, my brother proved himself to be exceptional. He had a natural aptitude for all aspects of design – graphic, interior, and architectural. His houses were not only unique, they were beautifully proportioned, immensely livable, and being custom-designed, sold for exceptionally high prices.

My mother has never stopped telling her children that family is more important than anything, that we must always help each other because we are only here for a number of years and when we die, thatʼs it. When we were older, she allowed us to use her available Secured-Line-of Credit accounts. This helped us take advantage of the real estate market when it was hot. Our banker told me once, that in her twenty plus years in banking, she had never met a family as tight as ours as we used each other credit lines freely and whoever used the money repaid the interest charges. Our family would not have prospered so quickly if we hadnʼt done this. I feel that we all owe our individual success on our togetherness and on the trust our mother placed in us which, in turn, taught us to trust each other.

My mother is one of the most generous people I know. She believes that the giver is more fortunate then the receiver because one has to have something in order to give something.

A few years before her mother died, mom would give her money to play the slot machines at casinos. Grandma loved the slots and, although mom did not understand why her mother liked them so much, she was happy to give, knowing that her mother was having a good time. Ironically, ten years ago, mom started playing the slots and the glow I see in her eyes when she is winning, is identical to the glow that I saw in my grandmotherʼs eyes.

History repeats itself. As my mother gave my grandmother financial support to play in casinos, I am now leading my mother to local casinos and Vegas to play. I purposely make the time to do this regularly because, although I do not understand why she finds the slots so exciting, it makes me happy to see her happy.

Although she never accepts money from me outside the casino, she accepts the chips I give her inside as I tell her that they are part of my blackjack winnings, and that she is playing with casino money. (I told my grandmother the same thing.) I wonder if twenty years from now, I will find myself attracted to the slots and my daughter will repeat the cycle, taking me to Vegas or local casinos, sharing her winning chips, just to catch the same glow in my eyes?

PART FIVE: Mother Remarries

Mom wasnʼt especially happy in her first marriage. She had wanted to leave my father, after he beat her, when she was pregnant with me, and had been angry with him when he refused to help when her twin boys were sick. If he hadnʼt talked her into coming with him to Canada, she would have sought sponsorship in the United States and left him. Although she knows he was a good man who did become more loving and supportive once the family arrived in Canada, their relationship was never easy.

After he died, she found it difficult raising four children by herself but she decided that it was easier than having a new partner who might not love her children as fiercely as she did. She worried too that he might mistreat them. Older generation Chinese believe that stepfathers are often abusive to children who arenʼt their own flesh and blood, and so she didnʼt want to put her children at risk.

Only when her youngest child was twenty-four, after being a widow for eighteen years, did my mother decide to start dating. I imagine that she was lonely. She was definitely lovely. At fifty-two years, she had kept her youthful figure, her smooth porcelain skin, and, because of her height – 5ʼ6” (tall for an Asian woman) – she wore clothes well. She favoured skirts and dresses that, I think, made her look elegant. The only time I remember her wearing pants was when she worked in the kitchen or on construction sites. Numerous men were attracted to her.

She was introduced to Wilfred Kwong who is known as “Fred” through Amy, a friend of a friend. Uncle Fred had opened a Senior Daycare Centre in Richmond. After studying two years for a license (the only Chinese to receive one), Uncle Fred was told by the city of Richmond that it couldnʼt provide the promised funding to help run his business. Unless he found outside investors, he would have to shut down. Uncle Fred was passionate about his centre, believing it contributed an essential service for senior citizens. He went to an immigration consultant, named Amy, in the hope that she could put him in touch with potential investors. Amy was so moved by Uncle Fredʼs predicament that she gave him my motherʼs telephone number.

She had given Uncle Fred my momʼs number for two reasons. Firstly, she hoped my mother would invest in the kind- hearted manʼs business and secondly, as she ran a match-making service on the side, she hoped that my mother would agree to date him. Uncle Fred telephoned the next day, and my mother agreed to go to the senior centre with him but, after the visit, she decided that she wasnʼt interested in investing. She couldnʼt see such a centre paying a good financial return on her money. She was also not interested in dating the man, having felt there was no chemistry between them.

When she telephoned Amy, demanding why she thought that they would be a good match, Amy insisted they were perfect for each other. “Trust me. He is the last living human with that size of heart. He is divorced and a good man.” Although mom thought that nothing would come of it, she reluctantly agreed to go on a casual date with Uncle Fred.

As she got to know him, she found she liked the tall handsome stranger who always dressed in a suit and tie and was a perfect gentleman. When she interviewed seniors from his daycare, they said that Uncle Fred treated them better than their own children. He drove them to church and to doctorsʼ appointments. He kept them company. He assisted those who had trouble eating. He helped them in any way, at whatever time they needed his assistance. Mom was so touched by the seniorsʼ stories about Uncle Fredʼs kindness that she took him to meet her siblings. They all loved him and convinced her that he was the best of the four men she was casually dating at the time. As mom always took her familyʼs advice seriously, she decided to date Uncle Fred exclusively. (All four of the men had known about the othersʼ existence and had been vying for momʼs attention.)

The more she got to know Uncle Fred, the more she admired the man. He was well-educated and informed: he had to read a newspaper everyday to know what was happening in the world. He had great taste and enjoyed shopping for clothes for mom and himself. She liked having a man at her side who acted as her protector, after so many years alone. She knew too that Uncle Fred admired her, and she liked that he was persistent and pursued her. Two years later, she agreed to marry him.

She wore white when she married Wilfred Kwong on October 13, 2002. We, her children, called her new husband “Uncle Fred.” Before the wedding, she had sold her restaurant and semi-retired so she and Uncle Fred could travel and enjoy themselves.

After three years of marriage, Uncle Fred began suffering from kidney problems. My mother and he flew to Guangzhou, China so he could have a kidney replaced. While he recuperated, she never left his side. They were together twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, for three months. When they arrived back in Canada, I could see that they were more in love than ever.

My mother was so happy. She thought that now they were guaranteed of, at least, twenty good years to travel the world together.

Mom told me recently that if her children deserted her, sheʼd be sad but if Uncle Fred left her, sheʼd be devastated. Since her children are all busy with their own lives, Uncle Fred is her constant companion. He is the one who is always ready to listen to her. As her road sense is less than perfect, he is the one who drives her wherever she wants to go. Although she has lived in Canada thirty-two years, she still has difficulty with the English language, so Uncle Fred has become her translator. She feels, without him, she would be deaf, mute, and blind. She calls him “her companion in old age”.

Five years after his first transplant, Uncle Fredʼs health deteriorated once again. His diabetes and high blood pressure were worse, and his kidneys were failing again. On April 7, 2011, he and my mother flew to China for a second transplant. Although the operation was more difficult than the first, Uncle Fred pulled through and he and mom flew back to Vancouver on May 9, 2011. I truly believe that my mom and uncle Fred are happy together.

Although he has three children from his first marriage, he often tells others that he has seven children and eleven grandchildren – ten of which are my motherʼs.

My mother loves having photographs taken, especially at family get-togethers. Whether itʼs a birthday, wedding, Christmas, Thanksgiving, or Motherʼs Day, my mother is ready to pose for the camera and then wants her family to pose around her. She feels, as I do, that pictures capture memories that no one can take from her. I have seen her sitting looking over old albums for hours,

sometimes smiling at captured memories when she was happy and sometimes in tears for those in the picture who have died. Nothing is more important to her than her family and she wants us close. When she overheard me saying that I wanted my daughter to go away to university, she cried. She understands but still she canʼt hold back the tears. She has been separated from too many loved ones too many times in her life. To her, family is everything.

Appendix

I. Lan Anh Vuong

| 1948 | – born in Haiphone |

| 1966 | – married Tung Bun Lee |

| 1968 | – first child, Julie born |

| 1970 | – second daughter Amy born |

| 1973 | – twin sons, Eric and Ming born |

| 1975 | – Ming died of pneumonia |

| 1976 | – third daughter Lisa born |

| 1977 | – left Vietnam for China |

| 1978 | – family in Hong Kong (Kai Tak East Refugee Camp in Kowloon |

| 1979 | – family arrive in Vancouver, Canada |

| 1981 | – Tung Ban Lee diagnosed with cancer |

| 1982 | – Lana begins work at Kinja Garden Japanese Restaurant in White Rock – Tung Bun Lee dies |

| 1984 | – Lana buys Sanuki Japanese Restaurant in North Delta |

| 1987 | – Lana pays balance of debt on restaurant |

| 1988 | – buys first lot in Surrey for 40, 000 |

| 1992 | – moves real estate activities to East Vancouver |

| 2000 | – starts dating |

| 2002 | – marries Wilfred Kwong – sells Sanuki Restaurant and semi-retires |

| 2005 | – flies to Guangzhou with Fred for his kidney transplant |

| 2008 | – Lana fully retires at 60 years old |

| 2011 | – returns to Guangzhou with Fred for his second kidney transplant |

II. Letter written by Tung Bun Lee

Dear Sponsors, brother and sister,